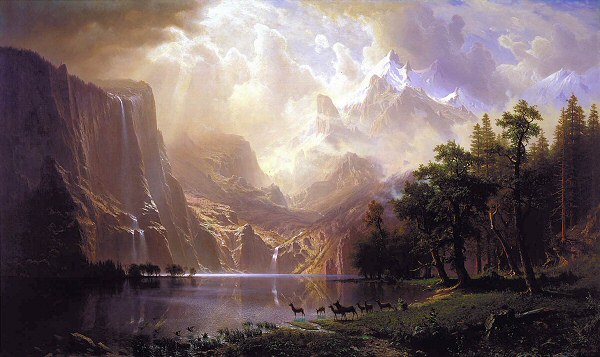

There is no doubt Albert Bierstadt’s dramatic landscape Bridal Veil Falls (circa 1871-1873) is among the highlights of the American collection at the NCMA. The painting’s majestic waterfall and idyllic pastoral foreground have a quiet kind of beauty. Landscape is, after all, a rather traditional format – one we modern viewers may find familiar or even somewhat conventional. But let us pause here again for a second look at what this work has to teach us about how those in the artist’s time understood America, its powerful geography, and its promise as a nation.

The nineteenth century in global history saw the golden age of European colonialism in Asia and Africa. Looking to keep pace with imperial economies and influence, the United States – a comparatively young country – sought to claim its own identity as a nation of power and promise. For many, the key to securing the nation’s place in the world lay in a geographic trope; that boundless opportunity personified in the untrammeled wilderness of the American West. Writing in 1845, prominent editor John Louis Sullivan proclaimed that, as a nation, it was “our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” The conquering of the West had become a symbol of American destiny – a national epic yet to be written.

The year is 1857. A young Albert Bierstadt has just returned to New Bedford, Massachusetts from Dusseldorf where he trained as a painter. Joining his fellow landscape artists of the prominent Hudson River School, Bierstadt began his career painting pastoral scenes from New England and upstate New York. Growing furor in the American imagination over Western promise, however, soon had its draw on Bierstadt and the artist made the necessary arrangements to join an expedition bound for California.

Embarking in 1859 on the first of many journeys westward he was to undertake throughout his career, Bierstadt carried with him a letter of introduction from then U.S. Secretary of War John B. Floyd. In the company of a wagon party of U.S. government surveyors, explorers, and various military personnel, Bierstadt paused to sketch mountain vistas, prairies, waterfalls, and other natural marvels along the way. In correspondence dated March 1, 1860, expedition leader Colonel Frederick W. Lander praised Bierstadt’s stereoscopic sketches as “highly valuable” and greatly “interesting to the country”.

Envision America in the middle of the nineteenth century. It was a time in which the Western landscape was yet relatively unknown to the population. Few had ventured west of the Mississippi as the rough terrain, limited infrastructure, and dramatic seasonal weather made westward travels especially arduous. Even with the advent of the First Transcontinental Railroad more than a decade later, the splendors of the Tetons, Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Grand Canyon, among others, held a mythic place in the American imagination.

Upon his return to New York, Albert Bierstadt quickly rose to prominence as a nationally-acclaimed landscape painter and was elected to the National Academy in 1860. Subsequent trips to Yellowstone and Yosemite in the 1870s provided material for a number of Bierstadt’s most famous paintings, which some contend were instrumental in inspiring Congress to pass the 1872 Yellowstone Park Bill; legislation that formally created the world’s first national park.

In his paintings, Bierstadt provided the American public with a window to the unknown West, inspiring awe at the majesty of a landscape that had come to be synonymous with the national future. For a traveler witnessing these landscapes for the first time, the experience must surely have been an emotional one. And Bierstadt’s works convey that emotion; an immensity and sense of wonder that imbue landscape with power. In the 1870s, that power inspired and motivated the American public, cementing a place for geography in the national consciousness.

Though Bierstadt’s later critics panned his romanticized interpretation of the American wilderness and, on the national stage, ‘Manifest Destiny’ gave way to new political conversations, the significance of the his work was in no way diminished. Albert Bierstadt himself was a product of the once popular Romantic school; a style that embraced evocative sentimentality and emotion as a critique of those logic-driven ways of thinking promulgated in the arts during the Enlightenment era.

The story of Bridal Veil Falls, as with much of Bierstadt’s work, is one of nationalism, American exceptionalism, and the westward mandate brought to life in nature. Bierstadt was no ordinary artist; he was an adventurer, an idealist, a romantic, and, perhaps most of all, a product of his time. Similarly, Bridal Veil Falls is no ordinary landscape. Rather, it is an epic metaphor for geographic nationalism and the American Edenic myth; a metaphor whose power in Bierstadt’s own lifetime lay in its ability to parallel the United States’ hope for its future in our modern world.